Breast cancer

Highlights

Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines

Experts continue to review new information on the timing and type of breast imaging studies to best reduce the toll of breast cancer. At this point, recommendations vary, and each woman should discuss options with her doctors to arrive at the plan that best matches her individual needs and preferences.

- Most guidelines recommend annual mammograms for women starting at age 40. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women at average risk for breast cancer have mammograms once every 2 years beginning at age 50.

- Women at high risk for breast cancer because of BRCA mutations, family history, or other factors, should have an MRI along with a mammogram every year.

FDA Withdraws Bevacizumab (Avastin)for Breast Cancer

In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revoked bevacizumab’s (Avastin) indication for treatment of metastatic breast cancer citing the drug’s lack of effectiveness and safety. Data indicate that bevacizumab does not significantly improve patients’ survival time and that its risks outweigh its benefits. Bevacizumab remains approved for treating other types of cancer.

Drug Approvals

Two new drugs were approved in 2012:

- Pentuzumab (Perjeta) is the newest treatment for advanced HER2-positive breast cancer.

- Everolimus (Afinitor) is approved for advanced hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Introduction

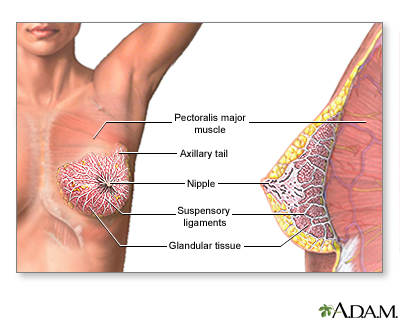

Breast cancers are potentially life-threatening malignancies that develop in one or both breasts. The structure of the female breast is important in understanding this cancer:

- The interior of the female breast consists mostly of fatty and fibrous connective tissues.

- It is divided into about 20 sections called lobes.

- Each lobe is further subdivided into a collection of lobules, structures that contain small milk-producing glands.

- These glands secrete milk into a complex system of tiny ducts. The ducts carry the milk through the breast and converge in a collecting chamber located just below the nipple.

- Breast cancer is either noninvasive (referred to as in situ, confined to the site of origin) or invasive (spreading).

Noninvasive Breast Cancer

Noninvasive breast cancers include:

- Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS; also called intraductal carcinoma). DCIS consist of cancer cells in the lining of the duct. DCIS is a non-invasive, early cancer, but if left untreated it may sometimes progress to an invasive, infiltrating ductal breast cancer. DCIS is the most common type of noninvasive breast cancer.

- Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Although it is technically not a cancer, lobular carcinoma in situ is a marker for an increased risk of invasive breast cancer.

A diagnosis of these early cancers (DCIS and LCIS) is made when there is no evidence of invasion.

Invasive Breast Cancer

Invasive cancer occurs when cancer cells spread beyond the basement membrane, which covers the underlying connective tissue in the breast. This tissue is rich in blood vessels and lymphatic channels that are capable of carrying cancer cells beyond the breast. Invasive breast cancers include:

- Invasive (also called infiltrating) ductal carcinoma. This type of invasive breast cancer penetrates the wall of a milk-passage duct. It accounts for 70 - 80% of all breast cancer cases.

- Invasive (also called infiltrating) lobular carcinoma. This is invasive cancer that has spread through the wall of a milk-producing lobule. It accounts for 10 - 15% of all breast cancers. It may appear in both breasts, sometimes in several separate locations.

There are other less common breast cancers that are not discussed in this report.

Risk Factors

About 12% of women will develop invasive breast cancer in their lifetime. Each year in the United States, about 230,000 women are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. Although breast cancer in men is rare, about 2,000 American men are diagnosed each year with invasive breast cancer.

There are many different risk factors for breast cancer.

Age

Most cases of breast cancer occur in women older than age 60. According to the American Cancer Society, about 1 in 8 cases of invasive breast cancer are found in women younger than age 45, while 2 in 3 cases of invasive breast cancer occur in women age 55 and older.

Race and Ethnicity

Breast cancer is slightly more common among white woman than African-American, Asian, Latina, or Native American women. However, African-American women tend to have more aggressive types of breast cancer tumors and are more likely to die from breast cancer than women of other races. It is unclear whether this is mainly due to biologic or socioeconomic reasons. Social and economic factors make it less likely that African-American women will be screened, so they are more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage. They are also less likely to have access to effective treatments.

Breast cancer is also more prevalent among Jewish women of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) descent (see Genetic Factors, below).

Family and Personal History

Women who have a family history of breast cancer are at increased risk for developing breast cancer themselves. Having a first-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) who has been diagnosed with breast cancer doubles the risk for developing breast cancer.

Women who have had ovarian cancer are at increased risk for developing breast cancer. And, a personal history of breast cancer increases the risk of developing a new cancer in the same or other breast.

Genetic Factors

About 5 - 10% of breast cancer cases are due to inherited genetic mutations.

BRCA Genes. Inherited mutations in genes known as BRCA1 or BRCA2 are responsible for most cases of hereditary breast cancers, ovarian cancers, or both in families with a history of these cancers.

BRCA gene mutations are present in only about 0.5% of the overall population. However, certain ethnic groups -- such as Jewish women of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) descent -- have a higher prevalence (2.5%) of BRCA gene mutations. BRCA gene mutations are also seen in some African-American and Hispanic women.

Screening Guidelines for BRCA Genes. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that women at high risk should be tested for BRCA genes, but does not recommend routine genetic counseling or testing in low-risk women (no family history of BRCA 1 or 2 genetic mutations). Risk assessment is based on a woman’s family history of breast and ovarian cancer (on both the maternal and paternal sides).

In general, a woman is considered at high risk for BRCA genes if she has a first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or sister) or several second-degree relatives (grandmother, aunt) diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer. Women who do not have a family history of breast cancer have a low probability of inheriting BRCA genes and do not need to be tested.

The relevance of the inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations to survival is controversial. Some studies have suggested that these mutations are linked to less lethal breast cancer. Others suggest that they do not change prognosis or may worsen it. Women with these genetic mutations do have a greater risk for a new cancer to develop. Patients with BRCA1 mutations tend to develop tumors that are hormone receptor negative, which can behave more aggressively.

Other Genetic Mutations. Other genes associated with increased hereditary breast cancer risk include p53, CHEK2, ATM, and PTEN. Researchers are continuing to make progress in discovering genetic variants of breast cancer. A recent study identified a subtype that appears to share similarities with ovarian cancer and may benefit from similar treatments. The hope is that these genetic analyses can lead to more targeted and precise drug treatments .

Exposure to Estrogen

Because growth of breast tissue is highly sensitive to estrogens, the more estrogen a woman is exposed to over her lifetime, the higher her risk for breast cancer.

Duration of Estrogen Exposure. Early age at menarche (first menstrual period) or later age at menopause may slightly increase a woman’s risk for breast cancer.

Pregnancy. Women who have never had children or who had their first child after age 30 may have a slightly increased breast cancer risk. Having children at an early age, and having multiple pregnancies, reduces breast cancer risk. Scientific evidence shows there is no association between abortion and increased breast cancer risk.

Studies have been mixed on whether breastfeeding decreases breast cancer risk. Breastfeeding reduces a woman's total number of menstrual cycles, and thereby estrogen exposure, which may account for its possible protective effects. Some studies suggest that the longer a woman breast-feeds, the lower her risk, and that breastfeeding may be most protective for women with a family history of breast cancer.

Birth Control Pills. Although studies have been conflicting about whether estrogen in oral contraceptives increase the chances for breast cancer, the most recent research indicates that current or former oral contraceptive use does not significantly increase breast cancer risk. Women who have used oral contraceptives may have slightly more risk for breast cancer than women who have never used them, but this risk declines once a woman stops using birth control pills.

Hormone Replacement Therapy. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) uses either estrogen alone (known as estrogen therapy [ET]) or estrogen in combination with progestogen (known as EPT or combination hormone therapy):

- Estrogen-progestogen therapy (EPT) is used by women who have a uterus, because estrogen alone can increase the risk of uterine cancer. EPT significantly increases the risk for developing and dying from breast cancer, especially when used for more than 5 years.

- Estrogen-only therapy (ET) is prescribed for women who have had a hysterectomy and do not have a uterus. ET does not appear to increase the risk for breast cancer. In fact, some studies indicate that ET may reduce breast cancer risk. However, prolonged used of ET can increase the risk for other health problems including blood clots, heart attack, stroke, and possibly ovarian cancer.

- Hormone therapy (EPT or ET) should not be used by women at high risk for breast cancer.

In general, most doctors recommend that women use HRT only for short-term (1 -2 years) relief of menopausal symptoms. Current guidelines advise initiating hormone therapy around the time of menopause only when women are in their 40s or 50s. Starting HRT past age 59 may increase the risk for breast cancer and other health problems.

Women who take HRT should be aware that they need regular mammogram screenings, because HRT increases breast cancer density, making mammograms more difficult to read. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #40: Menopause.]

Infertility and Infertility Treatments. Despite some concerns that infertility treatments using the drug clomiphene may increase the risk for breast cancer, most studies do not show an association. Some studies indicate that ovulation induction with clomiphene may actually decrease breast cancer risk. (Clomphine is related to tamoxifen, a drug that is used for breast cancer prevention in high-risk women.)

Breast Conditions

Certain breast conditions may increase the risk for breast cancer:

- Dense breast tissue is associated with a higher risk for breast cancer. Studies suggest that women with highly dense tissue have 2 - 6 times the risk of women with the least dense tissue. Genetic factors play a large role in breast density. Hormone replacement therapy also increases breast density. In addition, dense breasts make mammograms more difficult to read, which increases the likelihood of missing early signs of cancer.

- Benign proliferative breast disease, or unusual cell growth known as atypical hyperplasia, is a significant risk factor for breast cancer.

Some common benign breast abnormalities that pose very little or no risks for breast cancer include:

- Cysts. These mostly occur in women in their middle-to-late reproductive years and can be eliminated simply by aspirating fluid from them.

- Fibroadenoma. These are solid benign lumps that occur in women ages 15 - 30.

- Breast abscesses during breastfeeding.

- Nipple discharge. Discharge from the nipple is worrisome to patients, but it is unlikely to be a sign of cancer. Unexplained discharge still warrants evaluation, however.

- Mastalgia. This is breast pain that occurs in association with, or independently from, the menstrual cycle. About 8 - 10% of women experience moderate-to-severe breast pain associated with their menstrual cycle. In general, breast pain does not need assessment unless it is severe and prolonged.

Physical Characteristics

The following physical characteristics have been associated with increased risk:

- Obesity increases the risk for all types of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Women who gain weight after menopause are most at risk. (On a positive note, losing weight after menopause decreases breast cancer risk.) In postmenopausal women, estrogen is produced in fat tissue. High amounts of fatty tissue increase levels of estrogen in the body, leading to faster growth of estrogen-sensitive cancers.

- Estrogen is involved in building bone mass. Therefore, women with heavy, dense bones are likely to have higher estrogen levels and to be at greater risk for breast cancer.

- Some studies have found a greater risk for breast cancer in taller women, possibly due to the higher estrogen levels associated with greater bone growth.

Environmental Factors

Exposure to Estrogen-like Industrial Chemicals. Chemicals with estrogen-like effects, called xenoestrogens, have been under suspicion for years. There has been particular concern with pesticides containing organochlorines (DDT and its metabolites, such as dieldrin) and pyrethroids (permethrin), but at this time evidence of any causal association is very weak.

Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol. Women who took diethylstilbestrol (DES) to prevent miscarriage have a slightly increased risk for breast cancer. There may also be a slightly increased risk for their daughters (commonly called "DES daughters"), who were exposed to the drug when their mothers took it during pregnancy.

Radiation Exposure. Heavy exposure to radiation is a significant risk factor for breast cancer. Girls who receive high-dose radiation therapy for cancer face an increased risk for breast cancer in adulthood. Low-dose radiation exposure before age 20 may increase the risk for women with BRCA genetic mutations. Women should avoid unnecessary and excessive exposure to medical radiation, including x-rays and CT scans.

Lifestyle Factors

Alcohol consumption is a risk factor for breast cancer, especially for women have two or more drinks a day.

Disproven Risk Factors

Antiperspirants or use of deodorants after shaving have not been linked with any higher risk for breast cancer. There is also no evidence that bras increase breast risk. Abortion does not increase risk.

Prevention and Lifestyle Factors

Exercise

Regular exercise, particularly vigorous exercise, appears to offer protection against breast cancer. Exercise can help reduce body fat, which in turn lowers levels of cancer-promoting hormones such as estrogen. The American Cancer Society recommends engaging in 45 - 60 minutes of physical activity at least 5 days a week.

Exercise can also help women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and may help reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Studies indicate that both aerobic and weight training exercises benefit the body and the mind, and improve quality of life for breast cancer survivors.

Dietary Factors

Despite much research on the association between diet and breast cancer, there is still little consensus. The best advice is to eat a well-balanced diet and avoid focusing on one "cancer-fighting" food. The American Cancer Society’s dietary guidelines for cancer prevention recommend that people:

- Choose foods, serving sizes, and caloric contents that promote a healthy weight.

- Eat 5 or more servings of fruits and vegetables each day.

- Choose whole grains instead of refined grain products.

- Limit consumption of processed and red meat.

- Women should limit alcohol consumption to 1 drink per day (women at high risk for breast cancer should consider not drinking alcohol at all).

For breast cancer survivors, the American Cancer Society recommends diets that include lots of fruits and vegetables, low amounts of saturated fat (from meat and high-fat dairy products), moderation in soy foods, and moderate or no alcohol consumption.

Here are results from recent studies evaluating diet and breast cancer, for preventing both the development of cancer and its recurrence:

- Fats. Research is still mixed on the role that fats, and which specific types of fats, play in breast cancer risk and prevention. According to results from the Women’s Health Initiative study of dietary fat and breast cancer, there is no definite evidence that a low-fat diet will help prevent breast cancer. However, the study suggested that women who normally eat a very high-fat diet may benefit by reducing their fat intake.

- Fruits and Vegetables. Fruits and vegetables are important sources of antioxidants, which may help protect against the tissue damage linked to increased cancer risk. Antioxidants include vitamin C, vitamin E, and carotenoids such as beta-carotene and lycopene. Richly colored fruits and vegetables -- not supplements -- are the best sources for these nutrients. These fiber-rich foods are an essential part of a healthy diet. However, it is not clear whether fruits and vegetables can specifically prevent breast cancer development or recurrence.

- Calcium and Vitamin D. Eating lots of foods rich in calcium and vitamin D (such as yogurt and milk) may modestly reduce the risk of breast cancer for premenopausal women. Low-fat or non-fat dairy products are a healthier choice than high-fat varieties.

- Soy. The American Cancer Society recommends that women with breast cancer eat only moderate amounts of soy foods and avoid taking dietary supplements that contain high amounts of isoflavones. Isoflavones are a type of phytoestrogen (estrogen-like plant chemical). There have been concerns that high intakes of soy may increase the risk of estrogen-responsive cancers such as breast cancer.

Specific Preventive Measures for High-Risk Women

Lifestyle Factors. Premenopausal women at higher risk, usually because of family history, should take as many preventive measures as possible, starting at an early age. The following lifestyle choices may be beneficial:

- Exercising and eating a healthy diet is the first essential rule.

- High-risk premenopausal women might choose alternatives to oral contraceptives and, if feasible, consider having children early in their life.

- High-risk postmenopausal women should consider not taking hormone replacement therapy.

- Any woman at high risk for breast cancer should consider avoiding alcohol or drinking very sparingly.

Tamoxifen and Raloxifene. Drugs known as selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMs) act like estrogen in some tissues but behave like estrogen blockers (anti-estrogens) in others. Two SERMs -- tamoxifen (Nolvadex, generic) and raloxifene (Evista) -- are approved for breast cancer prevention for high-risk women. Tamoxifen and raloxifene are not recommended as prevention for women at low risk for breast cancer or its recurrence. Women at high risk for breast cancer should discuss with their doctors the risks and benefits of SERMs.

Preventive Surgery. Certain women who have a very high risk for breast cancer, due to factors such as BRCA genetic mutations or strong family history of breast cancer, may consider preventive (prophylactic) surgery. For these women, prophylactic mastectomy of both breasts can reduce the risk of cancer by as much as 97%. Prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes) can halve the risk for breast cancer and also significantly reduce the risk for ovarian cancer. Preventive surgery requires careful and serious consideration, and you should be sure to seek a second opinion from an oncologist before making a final decision.

Symptoms

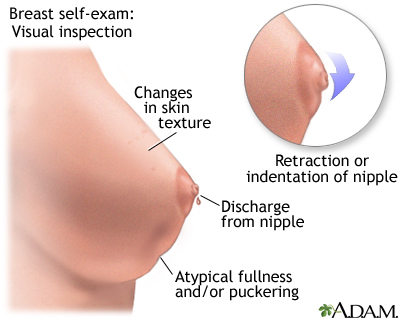

Breast cancers in their early stages are usually painless. Often the first symptom is the discovery of a hard lump. Half of such masses are found in the upper outer quarter of the breast. The lump may make the affected breast appear elevated or asymmetric. The nipple may be retracted or scaly. Sometimes the skin of the breast is dimpled like the skin of an orange. In some cases there is a bloody or clear discharge from the nipple.

Many breast cancers, however, produce no symptoms and cannot be felt on examination. With an increase in the use of mammogram screening programs during the last several decades, more breast cancers are being discovered before there are any symptoms.

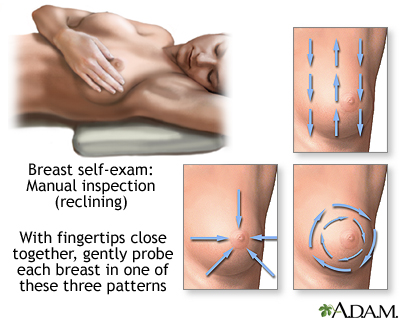

Monthly breast self-exams should always include: visual inspection (with and without a mirror) to note any changes in contour or texture, and manual inspection in standing and reclining positions to note any unusual lumps or thicknesses.

Diagnosis

Breast Examination by a Health Professional. Women ages 20 - 49 should have a physical examination by a health professional every 1 - 2 years. Those over age 50 should be examined annually.

Self-Examinations. Women are encouraged to perform self-examinations each month, but some studies have reported no difference in mortality rates between women who do self-examination and those who do not. This does not mean women should stop attempting self-examinations, but they should not replace the annual examination done by a health professional. Breast awareness may be as helpful as formal self exams as long as women who notice a breast abnormality obtain a professional evaluation promptly.

Monthly Self-Examination

1. Pick a time of the month that is easy to remember and perform self-examination at that time each month. The breast has normal patterns of thickness and lumpiness that change within a monthly period, and a consistently scheduled examination will help differentiate between what is normal from abnormal. Many doctors now recommend breast awareness rather than formal monthly self-examinations.

2. Stand in front of a mirror. Breasts should be basically the same size (one may be slightly larger than the other). Check for changes or redness in the nipple area. Look for changes in the appearance of the skin. With hands on the hips, push the pelvis forward and pull the shoulders back and observe the breasts for irregularities. Repeat the observation with hands behind the head. Move each arm and shoulder forward.

3. Lie down on the back with a rolled towel under one shoulder. Apply lotion or bath oil over the breast area. Using the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th finger pads (not tips) held together, make dime-sized circles. Press lightly first to feel the breast area, then press harder using a circular motion.

Using this motion, start from the collarbone and move downward to underneath the breast. Shift the fingers slightly over, slightly overlapping the previously checked region, and work upward back to the collarbone. Repeat this up-and-down examination until the entire breast area has been examined. Be sure to cover the entire area from the collarbone to the bottom of the breast area and from the middle of the chest to the armpits. Move the towel under the other shoulder and repeat the procedure.

Examine the nipple area, by gently lifting and squeezing it and checking for discharge.

4. Repeat step 3 in an upright position. (The shower is the best place for this, using plenty of soap.)

Note: A lump can be any size or shape and can move around or remain fixed. Of special concern are specific or unusual lumps that appear to be different from the normal varying thicknesses in the breast.

Mammograms

Current Recommendations for Screening. Mammography is a low-radiation screening method for breast cancer. Mammograms can detect early breast cancers when they are most curable. However, they can also raise alarm about cancer when it is not present (so-called false-positive results). In addition, mammograms can lead to treatments that do not improve a woman's outcome (so-called overdiagnosis). Experts disagree as to the relative benefits and risks of routine screening mammography. Because of this, there is debate on when women should begin to have mammograms and how frequently they should have them.

Most major professional groups, including The American Cancer Society and The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommend that women have a mammogram every year starting at age 40.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends:

- For women ages 40 - 49 years, the USPSTF does not recommend routine screening mammography. The decision to screen women in this age group should be made on a case-by-case basis, taking the patient's values regarding specific benefits and harms into account.

- For women ages 50 - 74 years, the USPSTF recommends that screening mammography be performed every other year.

Given the disagreement among experts, women, (particularly those in their 40s), should discuss the risks and benefits of mammography with their doctors, and then base their decisions on family history, general health, and personal values.

Mammograms in younger women produce a relatively high rate of false-positive results (when the test falsely indicates breast cancer), and there is a risk of radiation exposure and potentially unnecessary biopsies or surgeries. However, mammograms can help catch tumors while they are in their earliest and most treatable stages. The most deadly types of breast cancer tend to occur in women in their 40s.

To further complicate matters, not all early-stage breast cancers become life-threatening. With current science, doctors cannot predict if an untreated early-stage tumor will progress to a lethal stage. The issue of whether mammograms may contribute to overdiagnosis and overtreatment is very controversial and is currently a hot topic of debate among breast cancer researchers.

After a woman reaches age 50, her risk for developing breast cancer increases. (Women over age 65 account for most new cases of breast cancer.) Women with risk factors for breast cancer, including a close family member with the disease, should consider having annual mammograms starting 10 years earlier than the age at which the relative was diagnosed.

Other Imaging Techniques

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Ultrasound. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound techniques can detect very small tumors (less than half an inch). However, they are expensive and time-consuming procedures, and ultrasound may yield more false-positive results. Nevertheless, some doctors believe they are important in identifying small tumors missed on mammography in women who are receiving lumpectomy or breast-conserving surgeries. Such findings allow surgeons to remove the optimal amount of abnormal tissue. Ultrasound may be particularly helpful for women with dense breast tissue who show signs of breast cancer.

The American Cancer Society recommends that high-risk women have an MRI of their breast performed with their annual mammogram, including those who have:

- A BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation

- A first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, even if they have yet to be tested themselves

- A lifetime risk of breast cancer that has been scored at 20 - 25% or greater based on various risk assessment tools that evaluate family history and other factors

- Had radiation to the chest between ages 10 - 30

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Cowden syndrome, or Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, or may have one of these genetic syndromes based on a history in a first-degree relative

For women who have had cancer diagnosed in one breast, MRIs can also be very helpful for detecting hidden tumors in the other breast. An important study reported that MRI scans of women who were diagnosed with cancer in one breast detected over 90% of cancers in the other breast that had been previously missed by mammography or clinical breast exam. Currently, few women who are diagnosed with cancer in one breast are offered an MRI of the other breast. Some doctors advocate MRIs for all women newly diagnosed with breast cancer; others oppose this view. MRI scans may be most useful for younger women with breast cancer who have dense breast tissue that may obscure tumors from mammography readings. MRIs are less likely to be helpful for older women with early tumors in one breast and clear mammography readings in the other.

It is very important that women have MRIs at qualified centers that perform many of these procedures each year. MRI is a complicated procedure and requires special equipment and experienced radiologists. MRI facilities should also be able to offer biopsies when suspicious findings are detected.

Scintimammography. In scintimammography, a radioactive chemical is injected into the circulatory system, which is then selectively taken up by the tumor and revealed on mammograms. This method is used for women who have had abnormal mammograms or for women who have dense breast tissue. It is not used for regular screening or as an alternative to mammography.

Biopsy

A definitive diagnosis of breast cancer can be made only by a biopsy (a microscopic examination of a tissue sample of the suspicious area).

- When a lump can be felt and is suspicious for cancer on mammography, an excisional biopsy may be recommended. This biopsy is a surgical procedure for removing the suspicious tissue and typically requires general anesthesia.

- A core biopsy involves a small incision and the insertion of a spring-loaded hollow needle that removes several samples. The patient needs only a local anesthetic.

- A wire localization biopsy may be performed if mammography detects abnormalities, but there is no lump. With this procedure, using mammography as a guide, the doctor inserts a small wire hook through a hollow needle and into the suspicious tissue. The needle is withdrawn, and the hook is used by the surgeon to locate and remove the lesion. The patient may receive local or general anesthesia.

- A vacuum-assisted device may be used for some biopsies. This uses a single probe through which a vacuum is used to draw out tissue. It allows several samples to be taken without having to remove and re-insert the probe.

Final analysis of the breast tissue may take several days.

Sentinel Node Biopsy

The sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node that cancer cells are likely to spread to from the primary tumor (the original site of the cancer). Sentinel node biopsy is a procedure that examines the sentinel node to determine if cancer has spread.

Sentinel node biopsy involves:

- The procedure uses an injection of a tiny amount of a tracer, either a radioactively-labeled substance (radioisotope) or a blue dye, into the tumor site.

- The tracer or dye then flows through the lymphatic system into the sentinel node. This is the first lymph node to which any cancer would spread.

- The sentinel lymph node and possibly one or two others are then removed.

- If they do not show any signs of cancer, it is highly likely that the remaining lymph nodes will be cancer free, making further surgery unnecessary.

Patients who have a sentinel node biopsy tend to have better arm function and a shorter hospital stay than those who have an axillary node biopsy. The American Society of Clinical Oncology's guidelines recommend sentinel node biopsy instead of axillary lymph node dissection for women with early stage breast cancer who do not have nodes that can be felt during a physical exam.

Axillary Lymphadenectomy

If the sentinel node biopsy finds evidence that cancer has spread, the next diagnostic step is to find out how far it has spread. To do this, the doctor performs a procedure called an axillary lymphadenectomy, which partially or completely removes the lymph nodes in the armpit beside the affected breast (called axillary lymph nodes). It may require a hospital stay of 1 - 2 days.

Once the lymph nodes are removed, they are analyzed to determine whether subsequent treatment needs to be more or less aggressive:

- If no cancer is found in the lymph nodes, the condition is referred to as node negative breast cancer. The chances are good that the cancer has not spread and is still local.

- If cancer cells are present in the lymph nodes, the cancer is called node positive. Their presence increases the possibility that the cancer has spread microscopically to other areas of the body.

- In node-positive cases, it is still not known if the cancer has metastasized beyond the lymph nodes or, if so, to what extent. The doctor may perform further tests to see if the cancer has spread to the bone (bone scan), lungs (x-ray or CT scan) or brain (MRI or CT scan).

Side effects of the procedure may include increased risk for infection and pain, swelling in the arm from fluid build-up, and impaired sensation and restricted movement in the affected arm.

Prognosis

Breast cancer is the second most lethal cancer in women. (Lung cancer is the leading cancer killer in women.) The good news is that early detection and new treatments have improved survival rates. Unfortunately, women in lower social and economic groups still have significantly lower survival rates than women in higher groups.

Several factors are used to determine the risk for recurrence and the likelihood of successful treatment. They include:

- Location of the tumor and how far it has spread

- Whether the tumor is hormone receptor-positive or -negative

- Tumor markers

- Gene expression

- Tumor size and shape

- Rate of cell division

Women are now living longer with breast cancer. In the United States, there are currently more than 2.6 million breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer death rates have declined significantly in the past decade, especially for women younger than age 50. This decline may be due to better screening and better treatment options. However, survivors face the uncertainties of possible recurrent cancer and some risk for complications from the treatment itself.

Recurrences of cancer usually develop within 5 years of treatment. About 25% of recurrences and half of new cancers in the opposite breast occur after 5 years.

Location of the Tumor

The location of the tumor is a major factor in outlook:

- If the cancer is ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or has not spread to the lymph nodes (node negative), the 5-year survival rates with treatment are up to 99%.

- If the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or beyond the primary tumor site (node positive), the 5-year survival rate is about 84%.

- If the cancer has spread (metastasized) to other sites (most often the lung, liver, and bone), the average 5-year survival rate is 23%. New drug therapies, particularly aromatase inhibitors, have helped prolong survival for women with metastatic (stage IV) cancer.

The location of the tumor within the breast is an important predictor. Tumors that develop toward the outside of the breast tend to be less serious than those that occur more toward the middle of the breast.

Hormone Receptor-Positive or -Negative

About two-thirds of breast cancer cells contain receptors, or binding sites, for the hormones estrogen and progesterone.

- Estrogen receptor-positive (ER-positive, or ER+) breast cancer means that estrogen stimulates the growth of the cancer cells.

- Progesterone receptor-positive (PR-positive, or PR+) means that progesterone stimulates the growth of the cancer cells.

- Breast cancer is considered hormone receptor-positive if the cells have receptors for one or both of these hormones. About 75% of all breast cancers are estrogen receptor-positive. Most breast cancers that are ER+ are also PR+.

- Breast cancer is considered hormone receptor-negative if the cells lack these receptors. About 25% of breast cancers are hormone receptor-negative.

Hormone receptor-positive cancer is also called "hormone sensitive" because it responds to hormone therapy such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. Hormone receptor-negative tumors are referred to as "hormone insensitive" or "hormone resistant."

Women have a better prognosis if their tumors are hormone receptor-positive because these cells grow more slowly than receptor-negative cells. In addition, women with hormone receptor-positive cancer have more treatment options. (Hormone receptor-negative tumors can be treated only with chemotherapy.) Recent declines in breast cancer mortality rates have been most significant among women with estrogen receptor-positive tumors, due in part to the widespread use of post-surgical hormone-blocking therapy.

Tumor Markers

Tumor markers are proteins found in blood or urine when cancer is present. Although they are not used to diagnose cancer, the presence of certain markers can help predict how aggressive a patient’s cancer may be and how well the cancer may respond to certain types of drugs.

Tumor markers relevant for breast cancer prognosis include:

HER2. The American Cancer Society recommends that all women newly diagnosed with breast cancer get a biopsy test for a growth-promoting protein called HER2/neu. HER2-positive cancer usually occurs in younger women and is more quickly-growing and aggressive than other types of breast cancer. The HER2 marker is present in about 20% of cases of invasive breast cancer. Two types of tests are used to detect HER2:

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

- Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH)

Either test may be used as long as it is performed by an accredited laboratory. Tests that are not clearly positive or negative should be repeated.

Treatment with trastuzumab (Herceptin), lapatinib (Tykerb), or pentuzumab (Perjeta) may help women who test positive for HER2. A genetic test can help determine which patients with HER2-positive breast cancer may be good candidates for trastuzumab treatment.

Other Markers. Other markers that may be evaluated include CA 15-3, CA 27.29, CEA, ER, PgR, uPA, and PAI-1.

Gene Expression Profiling

Gene expression profiling tests (Oncotype DX, MammaPrint) examine a set of genes in tumor tissue to determine the likelihood of breast cancer recurrence. These tests are also used to help determine whether adjuvant (following surgery) drug treatments should be given. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that gene expression profiling tests be administered to newly diagnosed patients with node-negative, estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer (only Oncotype DX is approved for this use). Based on the results, a doctor can decide whether a patient who has had surgery may benefit from chemotherapy.

Other Factors for Predicting Outlook

Tumor Size and Shape. Large tumors pose a higher risk than small tumors. Undifferentiated tumors, which have indistinct margins, are more dangerous than those with well-defined margins.

Rate of Cell Division. The more rapidly a tumor grows, the more dangerous it is. Several tests measure aspects of cancer cell division and may eventually prove to predict the disease. For example, the mitotic index (MI) is a measurement of the rate at which cells divide. The higher the MI, the more aggressive the cancer. Other tests measure cells at a certain phase of their division.

Effect of Emotions and Psychological Support

Individual or group psychotherapy may be helpful for women with breast cancer who are suffering emotionally. On a reassuring note, stress has been ruled out as a risk factor for breast cancer development or recurrence.

Treatment

The three main treatments of breast cancer are:

- Surgery

- Radiation

- Drug therapy

No one treatment fits every patient, and combination therapy is usually required. The choice is determined by many factors, including the age of the patient, menopausal status, the kind of cancer (ductal verses lobular), its stage, and whether or not the tumor contains hormone receptors.

Breast cancer treatments are defined as local or systemic:

- Local Treatment. Surgery and radiation are considered local therapies because they directly treat the tumor, breast, lymph nodes, or other specific regions. Surgery is usually the standard initial treatment.

- Systemic Treatment. Drug treatment is called systemic therapy, because it affects the whole body. Drugs may include either chemotherapy or hormone therapy. Drug therapy may be used as primary therapy for patients for whom surgery or radiation therapy is not appropriate, neoadjuvant therapy (before surgery or radiation) to shrink tumors to a size that can be treated with local therapy, or as adjuvant therapy (following surgery or radiation) to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence. For metastatic cancer, drugs are used not to cure but to improve quality of life and prolong survival.

Any or all of these therapies may be used separately or, most often, in different combinations. For example, radiation alone or with chemotherapy or hormone therapy may be beneficial before surgery, if the tumor is large. Surgery followed by radiation and hormone therapy is usually recommended for women with early-stage, hormone-sensitive cancer. There are numerous clinical trials investigating new treatments and treatment combinations. Patients, especially those with advanced stages of cancer, may wish to consider enrolling in a clinical trial.

Cancer Stage and Treatment Options

Treatment strategies depend in part on the stage of the cancer.

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ). Stage 0 breast cancer is considered non-invasive (‘in situ"), meaning that the cancer is still confined within breast ducts or lobules and has not yet spread to surrounding tissues. Stage 0 cancer is classified as either:

- Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). These are cancer cells in the lining of a duct that have not invaded the surrounding breast tissue.

- Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). These are cancer cells in the lobules of the breast. LCIS rarely develops into invasive breast cancer, but having it in one breast increases the risk of developing cancer in the other breast.

Treatment options for DCIS include:

- Breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy (followed by hormone-blocking therapy for women with hormone-sensitive cancer). Many doctors recommend this approach.

- Total mastectomy (followed by hormone-blocking therapy for women with hormone-sensitive cancer)

- Breast-conserving surgery without radiation therapy

Treatment options for LCIS include:

- Regular exams and mammograms to monitor any potential changes (observation treatment)

- Hormone-blocking therapy to prevent development of breast cancer (for women with hormone-sensitive cancer)

- Mastectomy of both breasts was previously used as treatment, but is now rarely recommended

Stage I and II (Early-Stage Invasive). In stage I cancer, cancer cells have not spread beyond the breast, and the tumor is no more than 2 cm (about 3/4 of an inch) across.

Stage II cancer is classified as either stage IIA or stage IIb.

In stage IIA cancer the tumor is either:

- No more than 2 centimeters and has spread to the underarm lymph nodes (axillary lymph nodes)

- Between 2 - 5 centimeters and has not spread to the underarm lymph nodes

In stage IIB cancer the tumor is either:

- Larger than 2 centimeters and less than 5 centimeters and has spread to 1 - 3 axillary lymph nodes

- Larger than 5 centimeters but has now spread to lymph nodes

Treatment options for stage I and stage II breast cancer may include:

- Breast-conserving surgery (such as lumpectomy) followed by radiation therapy

- Modified radical mastectomy with or without breast reconstruction

- Post-surgical therapy (adjuvant therapy), including radiation of lymph nodes, chemotherapy, or hormone-blocking therapy

- Trastuzumab (Herceptin) given along with or following adjuvant chemotherapy for women with HER2-positive cancer

Stage III (Locally Advanced). Stage III breast cancer is classified into several sub-categories: Stage IIIA, stage IIIB, and stage IIIC (operable or inoperable).

In stage IIIA breast cancer, the tumor is either of the following:

- Not more than 5 centimeters and has spread to axillary lymph nodes

- Larger than 5 centimeters and has spread to axillary nodes or to internal mammary nodes.

Treatment options for stage IIIA breast cancer are the same as those for stages I and II.

In stage IIIB breast cancer, the tumor has spread to either of the following:

- Tissues near the breast (including the skin or chest wall)

- Lymph nodes within the breast or under the arm

Stage IIIB treatment options may include:

- Chemotherapy, and possibly hormone therapy (sometimes in combination with chemotherapy)

- Chemotherapy followed by surgery (breast-conserving surgery or total mastectomy) with lymph node dissection followed by radiation therapy and possibly more chemotherapy or hormone-blocking therapy

- Clinical trials

Stage IIIC breast cancer is classified as either operable or inoperable.

In operable stage IIIC, the cancer may be found in:

- 10 or more of the underarm lymph nodes

- Lymph nodes beneath the collarbone and near the neck on the same side of the body as the affected breast

- Lymph nodes within the breast as well as underarm lymph nodes

Treatment options for operable stage III breast cancer are the same as those for stage I and II breast cancers.

In inoperable stage III breast cancer, the cancer has spread to lymph nodes above the collarbone and near the neck on the same side of the body as the affected breast. Treatment options are the same as those for stage IIIB.

Stage IV (Advanced Cancer). In stage IV, the cancer has spread (metastasized) from the breast to other parts of the body. In about 75% of cases, the cancer has spread to the bone. The cancer at this stage is considered to be chronic and incurable, and the usefulness of treatments is limited. The goals of treatment for stage IV cancer are to stabilize the disease and slow its progression, as well as to reduce pain and discomfort.

Treatment options for stage IV cancer include:

- Surgery or radiation for any localized tumors in the breast.

- Chemotherapy, hormone-blocking therapy, or both. Targeted therapy with trastuzumab (Herceptin), lapatinib (Tykerb), or pentuzumab (Perjeta) should be considered for women with HER2-positive cancer.

- Cancer that has spread to the brain may require radiation and high-dose steroids.

- Cancer that has spread to the bone may be helped by radiation or bisphosphonate drugs. Such treatments can relieve pain and help prevent bone fractures.

- Clinical trials of new drugs or drug combinations, or experimental treatments such as high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell transplant.

Post-Treatment Care

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends follow-up care for patients who have been treated for breast cancer:

- Visit your doctor every 3 - 6 months for the first 3 years after your first cancer treatment, every 6 - 12 months during the fourth and fifth year, and once a year thereafter.

- Have a mammogram 1 year after the mammogram that diagnosed your cancer (but no earlier than 6 months after radiation therapy), and every 6 - 12 months thereafter.

- Perform a breast self-exam every month (however, this is no substitute for a mammogram).

- See your gynecologist regularly (women taking tamoxifen should be sure to report any vaginal bleeding).

- A year after diagnosis, you can either continue to see your oncologist or transfer your care to your primary care physician.

- If you are on hormone therapy, discuss with your oncologist how often to schedule follow-up visits for re-evaluation of your treatment.

ASCO does not recommend the use of laboratory blood tests (complete blood counts, carcinoembryonic antigen) or imaging tests (bone scans, chest x-rays, liver ultrasound, FDG-PET scan, CT scan) for routine breast cancer follow-up.

Genetic counseling may be helpful if you have:

- Ashkenazi Jewish heritage

- Personal or family history of ovarian cancer

- Personal or family history of cancer in both breasts

- Any first-degree female relative (mother, sister, daughter) diagnosed with breast cancer before age 50

- Two or more first-degree or second-degree (grandparent, aunt, uncle) diagnosed with breast cancer

- History of breast cancer in a male relative

Pregnancy after Breast Cancer Treatment. There are no definite recommendations on how long a woman should wait to become pregnant after breast cancer treatment. Because of the connection between estrogen levels and breast cancer cell growth, some doctors recommend delaying pregnancy until 2 years after treatment in order to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and improve odds for survival. However, other studies indicate that conceiving 6 months after treatment does not negatively affect survival. Discuss with your doctor your risk for recurrence, and when it may be safe to attempt pregnancy.

Recurrent Breast Cancer

Recurrent breast cancer is considered to be an advanced cancer. In such cases, the disease has come back in spite of the initial treatment. Most recurrences appear within the first 2 - 3 years after treatment, but breast cancer can recur many years later. Treatment options are based on the stage at which the cancer reappears, whether or not the tumor is hormone responsive, and the age of the patient. Between 10 - 20% of recurring cancers are local. Most recurrent cancers are metastatic. All patients with recurring cancer are candidates for clinical trials.

Because most breast cancer recurrences are discovered by patients in between doctor visits, it is important to notify your doctor if you experience any of the following symptoms. These symptoms may be signs of breast cancer recurrence:

- New lumps in the breast

- Bone pain

- Chest pain

- Abdominal pain

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Persistent headaches or coughing

- Rash on breast

- Nipple discharge

Surgery

Surgery is a part of nearly every patient's treatment for breast cancer. The initial surgical intervention is often a lumpectomy, the removal of the tumor itself. In the past, mastectomy (the removal of the breast) was the standard treatment for nearly all breast cancers. Now, many patients with early-stage cancers can choose breast-conserving treatment, or lumpectomy followed by radiation, with or without chemotherapy.

For invasive breast cancer, studies indicate that lumpectomy or partial mastectomy combined with radiation therapy works as well as a modified radical mastectomy.

Breast-Conserving Procedures

Breast-conserving procedures are considered as appropriate and as successful as mastectomy in most women with early stage breast cancer. All women should discuss these options fully with their doctor. Recurrence rates with conservative surgery are highest in women under age 45. Some women choose mastectomy over breast-conserving treatment even if the latter is appropriate because it gives them a greater sense of security and allows them to avoid radiation therapy.

Lumpectomy. Lumpectomy is the removal of the tumor, often along with lymph nodes in the armpit. It serves as an opportunity for biopsy, a diagnostic tool, and a primary treatment for small local breast tumors. If invasive cancer is found, the doctor will decide to proceed with breast radiation therapy, to remove additional tissue (should the margins of the specimen show signs of cancer), or to perform a mastectomy. Lumpectomy followed by radiation therapy is appropriate and as effective as mastectomy for most women with stage I or II breast cancers.

Breast-Conserving Surgery (Quadrantectomy). Breast-conserving surgery (sometimes referred to as quadrantectomy) removes the cancer and a large area of breast tissue, occasionally including some of the lining over the chest muscles. It is less invasive than a full mastectomy, but the cosmetic results are less satisfactory than with a lumpectomy. Studies have found that breast-conserving surgeries plus postoperative radiotherapy offer the same survival rates as radical mastectomy in most women with early breast cancer.

Mastectomy

Surgery to remove the breast (mastectomy) is important for women with operable breast cancer who are not candidates for breast conserving surgeries. There are different variations on the procedure:

- A total mastectomy involves removal of the whole breast and sometimes lymph nodes under the armpit.

- A radical mastectomy removes the breast, chest muscles, all of the lymph nodes under the arm, and some additional fat and skin. (A modified radical mastectomy removes the entire breast and armpit lymph nodes, with the underlying chest wall muscle.) For most patients, there are no survival advantages from radical mastectomy compared to less invasive mastectomies.

Complications and Side Effects of Surgery. Short-term pain and tenderness occur in the area of the procedure, and pain relievers may be necessary.

The most frequent complication of extensive lymph node removal is lymphedema, or swelling, of the arm. The likelihood of edema can be lessened by removing only some of the lymph nodes instead of all of them.

Infrequent complications include poor wound healing, bleeding, or a reaction to the anesthesia.

After mastectomy and lymph node removal, women may experience numbness, tingling, and difficulty in extending the arm fully. These effects can last for months or years afterward.

Breast Reconstruction

After a mastectomy, some women choose a breast prosthesis or opt for breast reconstruction, which can be performed at the time of the mastectomy itself, if desired. Several studies have indicated that women who take advantage of cosmetic surgery after breast cancer have a better sense of well-being and a higher quality of life than women who do not choose reconstructive surgery.

The breast is reshaped using a saline implant or, for a more cosmetic result, a muscle flap is taken from elsewhere in the body. Muscle flap procedures are more complicated, however, and blood transfusions may be required. If the nipple is removed, it is rebuilt from other body tissues and color is applied using tattoo techniques. It is nearly impossible to rebuild a breast that is identical to its partner, and additional operations may be necessary to achieve a desirable effect.

Implants, including silicone implants, do not appear to put a woman at risk for breast cancer recurrence. However, breast implants are not lifetime devices. About half of women who receive an implant for breast reconstruction will need to have it removed or replaced about 10 years after implantation.

Radiation

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays to kill cancer cells or to shrink the size of a tumor in the breast or surrounding tissue. It is used for several weeks following lumpectomy or partial mastectomy, and sometimes after full mastectomy. Radiation therapy can help reduce the chance of breast cancer recurrence in the breast and chest wall. Radiation is also important in advanced stages of cancer for relief of symptoms and to slow progression. Research shows that radiation therapy is helpful for women of all ages, including those over age 65.

Administration of Radiation Therapy

Radiation is generally administered in the following ways:

External Beam Radiation. This type of radiation is administered 4 - 6 weeks after surgery and delivered externally by an x-ray machine that targets radiation to the whole breast. It may be delivered to the chest wall in high-risk patients (large tumors, close surgical margins, or lymph node involvement). The treatment is generally given daily (except for weekends) for about 6 weeks. Some hospitals offer a shortened course of 3 weeks of radiation for patients with early-stage breast cancer.

Brachytherapy. Less commonly, radiation is delivered in implants (called brachytherapy). Implants are most often used as a radiation boost after whole breast radiation.

Side Effects of Radiation Therapy

Side effects of radiation include:

- Fatigue is very common and increases with subsequent treatments, but most women are able to continue with normal activities. Exercise may be helpful.

- Nausea and lack of appetite may develop and worsen as treatment progresses.

- Skin changes and burns can occur on the breast skin. Using a cream that contains a corticosteroid, such as mometasone furoate (MMF), may be helpful. After repeated sessions, the skin may become moist and "weepy." Exposing the treated skin to air as much as possible helps healing. Washing the affected skin with soap and water is not harmful.

- Uncommonly, the breast may change color, size, or become permanently firm.

- Rarely, the nearest arm may swell and develop impaired mobility or even paralysis.

Long-Term Complications

Future complications include:

- Radiation to the left breast may increase the long-term risk for developing heart disease and heart attacks.

- There is a very small risk (less than 1%) of lung irritation and scarring.

- Some studies have reported a higher risk for future cancer in the opposite breast in younger women who have been given radiation to the chest wall.

- Radiation therapy can increase the risk of developing other cancers, such as soft tissue malignancies known as sarcomas.

Current advanced imaging techniques use precise radiation that reduces exposure. These newer techniques are likely to reduce the risks for heart disease and other serious complications.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs are "cytotoxic" (cell-killing) drugs. They are given orally or by injection. They work systemically by killing cancer cells throughout the body. (Unfortunately, they also kill some normal cells, which accounts for many of their side effects.) Chemotherapy is always used for advanced breast cancer, but may also be used to treat types of early-stage breast cancer.

Newer biologic drugs target specific proteins involved in cancer. Treatment with these drugs is called targeted therapy. Because targeted therapy drugs do not work as systemically as chemotherapy or hormone-blocking drugs, they tend to cause fewer widespread side effects, although they also carry risks of their own

Chemotherapy needs to be tailored to the type of cancer involved. Women require different treatments depending on whether the tumor is node-negative or -positive, hormone receptor-positive or -negative, or HER2-positive or -negative. Different treatment approaches are also used for early-stage cancer and advanced cancer.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is administered following surgery and before radiation therapy. Delaying chemotherapy until more than 12 weeks after surgery may increase the risk for breast cancer recurrence and reduce the odds for survival.

Chemotherapy Drug Classes

Many different types of chemotherapy drugs are used to treat breast cancer. Common types of chemotherapy drug classes include:

- Anthracyclines include doxorubicin (Adriamycin, generic) and epirubicin (Ellence, generic). Anthracycline-based combination regimens are often used to treat early-stage breast cancer, as well as advanced cancer.

- Taxanes include paclitaxel (Taxol, generic) and docetaxel (Taxotere, generic). These drugs may be particularly helpful for node-positive breast cancer. A newer formulation of paclitaxel (Abraxane) is used as a secondary treatment for advanced breast cancer.

- Platinum-based drugs include oxaliplatin (Eloxatin, generic) and carboplatin (Paraplatin, generic). These drugs may be used in combination regiments for advanced cancer or for cancers associated with BRCA genes.

Chemotherapy Regimens for Early-Stage Breast Cancer

Some of the abbreviations used for chemotherapy drug combinations (regimens) refer to drug classes rather than drug names. For example, regimens that contain an anthracycline drug (such as doxorubicin) use the letter "A," and regimens that contain a taxane drug (such as docetaxel) use the letter "T." Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), fluorouracil (5-FU), and methotrexate (MTX) are standard cancer drugs used in many breast cancer chemotherapy regimens.

Chemotherapy regimens usually consist of 4 - 6 cycles of treatment given over 3 - 6 months. Common chemotherapy regimens for early-stage breast cancer include:

- AC (Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide)

- AC followed by T (Doxorubicin and cylophosphamide followed by paclitaxel)

- CAF (Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-FU)

- CMF (Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-FU)

- TAC (Docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide)

Chemotherapy for Advanced (Metastatic) Cancer

Patients who develop metastatic disease (cancer that spreads throughout the body) are generally not curable. New advances in drug therapies, however, can help shrink tumors, prolong survival, and improve quality of life.

Chemotherapy regimens for advanced cancer may use a single drug or a combination of drugs. Many chemotherapy regimens used for early-stage breast cancer are also used for advanced breast cancer. Some specific individual drugs and combinations for advanced cancer include:

- Gemcitabine and paclitaxel. Gemcitabine (Gemzar, generic) is used in combination with paclitaxel (Taxol, generic) as a first-line treatment option for women with metastatic breast cancer.

- Capecitabine (Xeloda) and docetaxel (Taxotere, generic). Capecitabine is an oral drug that is chemically related to 5-FU. In addition to combination treatment with docetaxel, it is used in combination with a new type of drug, ixabepilone (Ixempra), for patients with advanced breast cancer who have not responded to other types of chemotherapy. It is also being studied in combination with other drugs.

- Eribulin (Halaven) was approved in 2010 as a treatment for metastatic breast cancer in patients who have already received at least two regimens of chemotherapy for late-stage disease. The injectable drug is a synthetic compound of a chemical found in a type of sea sponge.

- Everolimus (Afinitor) was approved in 2012 for treatment of advanced hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Numerous chemotherapy drugs and drug combinations are being tested in clinical trials. Patients with advanced breast cancer may also receive other types of drug treatments. For example, bisphosphonate drugs such as zoledronic acid (Zometa) and pamidronate (Aredia, generic), and the biologic drug denosumab (Xgeva), are important supportive drugs for preventing fractures and reducing pain in people whose cancer has spread to the bones.

Targeted Therapy for Early-Stage HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

Trastuzumab (Herceptin). Trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody biologic drug that targets the HER2 protein on cancer cells. HER2-positive cancers account for 15 - 25% of early-stage breast cancer and are associated with more aggressive disease. Younger women tend to be most affected.

Trastuzumab is given along with other chemotherapy drugs following lumpectomy or mastectomy. Research indicates that trastuzumab can help prevent cancer recurrence and death among women with early-stage breast cancer, but it increases the risk of heart problems. Trastuzumab can cause heart failure. Women who have heart failure or weak heart muscle (cardiomyopathy) should not use this drug. Women who take trastuzumab need to have regular heart monitoring, especially if they have already have heart problems.

Targeted Therapy for Advanced HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

Three targeted therapy (biologic) drugs are approved for the treatment of HER2-positive advanced breast cancer:

- Trastuzumab (Herceptin) is used after chemotherapy, along with drugs such as paclitaxel.

- Lapatinib (Tykerb) is used in combination with capecitabine (Xeloda). Research suggests it may have fewer risks for heart problems than trastuzumab. Lapatinib is also approved for combination use with letrozole (Femara, generic) as a first-line treatment for hormone-positive and HER2-positive advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women for whom hormone treatment is recommended.

- Pentuzumab (Perjeta) is used in combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel for treatment of HER2 postive metastatic breast cancer. Pentuzumab is the newest type of anti-HER2 therapy.

Side Effects of Chemotherapy

Side effects occur with all chemotherapeutic drugs. They are more severe with higher doses and increase over the course of treatment.

Common side effects include:

- Nausea and vomiting. Drugs such as ondansetron (Zofran, generic) and aprepitant (Emend) can help relieve these side effects.

- Diarrhea

- Temporary hair loss

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- Depression

Serious short- and long-term complications can also occur and may vary depending on the specific drugs used. They may include:

- Anemia. Chemotherapy-induced anemia is usually treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs, which include epoietin alfa (Epogen, Procrit) and darberpetin alfa (Aranesp). Doctors need to follow strict dosing guidelines when administering these drugs. Patients should discuss the risks and benefits of erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs with their oncologists. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #57: Anemia.]

- Increased chance for infection from severe reduction in white blood cells (neutropenia). The addition of a drug called granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim and lenograstim) can help reduce the risk for severe infection.

- Liver and kidney damage.

- Abnormal blood clotting (thrombocytopenia).

- Allergic reaction, particularly to platinum-based drugs.

- Menstrual abnormalities and infertility. Premature menopause is a common side effect of chemotherapy. A hormone medication called a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue, which puts women in a temporary pre-pubescent state during chemotherapy, may preserve fertility in some women. Women may also wish to consider embryo cryopreservation -- the harvesting of eggs, followed by in vitro fertilization and freezing of embryos for later use. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends that women being treated for cancer see a reproductive specialist to discuss all available fertility preservation options.

- Sexual dysfunction.

- Rarely, secondary cancers such as leukemia.

- Some women report problems in concentration, motor function, and memory, which can be long-term.

- Heart problems. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) may increase the risk for heart failure, particularly in women with pre-existing risk factors. Cumulative doses of anthracyclines (doxorubicin, epirubicin) can also damage heart muscles over time and increase the risk for heart failure.

- Taxanes can cause a drop in white blood cells and possible problems in the heart and central nervous system. Taxane therapy may also cause severe joint and muscle pain in some patients.

Hormone Therapy

The goal of hormone therapy is to prevent estrogen from stimulating breast cancer cells. It is recommended for women whose breast cancers are hormone-receptor positive (either estrogen or progesterone), regardless of the size of the tumor and whether or not it has spread to the lymph nodes. Like chemotherapy, hormone therapy works systemically.

Hormone therapy works by blocking estrogen that causes cell proliferation. It is used only for patients with hormone receptor-positive ("hormone sensitive") tumors. Different types of hormone therapy work in different ways by:

- Blocking estrogen receptors in cancer cells (Tamoxifen)

- Suppressing estrogen production in the body (Aromatase inhibitors)

- Destroying ovaries, which produce estrogen (Ovarian ablation)

Tamoxifen was the first widely used hormonal therapy drug, but today it is mainly used as adjuvant therapy for premenopausal and perimenopausal women with hormone-sensitive breast cancer. Postmenopausal women are now usually prescribed aromatase inhibitors.

Tamoxifen and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs)

Tamoxifen (Nolvadex, generic) has been the standard hormonal drug used for breast cancer. It belongs to a class of compounds called selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). SERMs chemically resemble estrogen and trick the breast cancer cells into accepting it in place of estrogen. Unlike estrogen, however, they do not stimulate breast cancer cell growth. Because SERMs block estrogen’s effects on cancer cells, they are sometimes referred to as "anti-estrogen" drugs.

Tamoxifen is used for all cancer stages in (mainly premenopausal) women with hormone receptor-positive cancers. In addition, it is used to prevent breast cancer in high-risk women. Another SERM drug, toremifene (Fareston), is an option for women with advanced cancer, but this drug is rarely used in the United States. A third drug, fulvestrant (Faslodex), works in a similar anti-estrogen way to tamoxifen but belongs to a different drug class. Fulvestrant is approved only for postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive advanced breast cancer in whom tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors no longer work.

To prevent cancer recurrence, women should take tamoxifen for 5 years following surgery and radiation. Tamoxifen is an effective cancer treatment, but it can cause unpleasant side effects and has small (less than 1%) but serious risks for blood clots and uterine (endometrial) cancer. Immediately report any signs of vaginal bleeding to the doctor, as this may be a symptom of uterine cancer. Tamoxifen risks for blood clots may be higher for obese women.

Tamoxifen interacts with certain types of antidepressants. In particular, the antidepressants paroxetine (Paxil, generic) and fluoxetine (Prozac, generic) can weaken the effectiveness of tamoxifen. Doctors recommend venlafaxine (Effexor, generic) as a first-line antidepressant drug for women who take tamoxifen.

Less serious, but discomforting, side effects include hot flashes and mood swings. According to one study, nearly 25% of women stop taking tamoxifen within 1 year because of these symptoms. By 3.5 years, over 33% stop treatment. Taking tamoxifen for fewer than 5 years, however, increases the risk for cancer recurrence and death. Talk with your doctor about antidepressants or other therapies that may help you cope with tamoxifen’s side effects.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) current guidelines recommend that postmenopausal women switch to an aromatase inhibitor after 2 - 3 years of tamoxifen therapy. Postmenopausal women who have already completed 5 years of tamoxifen therapy can benefit from switching to an aromatase inhibitor for up to an additional 5 years to help further reduce their risk of cancer recurrence. Several recent studies have indicated that switching from tamoxifen to an aromatase inhibitor significantly improves survival rates and reduces the risk of death from breast cancer as well as other causes.

Aromatase Inhibitors

Aromatase inhibitors are recommended as first-line adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive breast cancer. Aromatase inhibitors are taken for up to 5 years. They can be used either before or after tamoxifen treatment. (If women begin and then discontinue aromatase inhibitors, they should consider switching to tamoxifen to complete the 5-year treatment.)

Aromatase inhibitors block aromatase, an enzyme that is a major source of estrogen in many major body tissues, including the breast, muscle, liver, and fat. Aromatase inhibitors work differently than tamoxifen. Tamoxifen interferes with tumors’ ability to use estrogen by blocking their estrogen receptors. Aromatase inhibitors reduce the overall amount of estrogen in the body.

Because these drugs cannot stop the ovaries of premenopausal women from producing estrogen, they are recommended only for postmenopausal women.

There are currently three aromatase inhibitors approved for treating early-stage, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women:

- Anastrazole (Armidex, generic)

- Exemestane (Aromasin, generic)

- Letrozole (Femara, generic)

There are no significant differences between these three drugs. Women who cannot tolerate one type of aromatase inhibitor can switch to a different one. All of these drugs are also approved for women with advanced (metastatic) hormone-sensitive breast cancer. Studies indicate that the introduction of aromatase inhibitors has helped greatly in prolonging survival for women with advanced cancer.

Compared to tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors are less likely to cause blood clots and uterine cancer. However, these drugs are more likely to cause osteoporosis, which can lead to bone loss and fractures. Women should have their bone mineral density monitored during aromatase inhibitor treatment. In general, recent studies indicate that aromatase inhibitors are better than tamoxifen in improving survival and reducing the risk of cancer recurrence. Unfortunately, like tamoxifen, they can cause hot flashes, as well as joint pain.

Ovarian Ablation

Ovarian ablation is a treatment that stops estrogen production from the ovaries. Medications can accomplish ovarian ablation. Destroying the ovaries with surgery or radiation can also shut down estrogen production. (Osteoporosis is one serious side effect of this approach, but several therapies are available to help prevent bone loss.)

Chemical Ovarian Ablation. Drug treatment to block ovarian production of estrogen is called chemical ovarian ablation. It is often reversible. The primary drugs used are luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists, such as goserelin (Zoladex). (They are also sometimes called GnRH agonists). These drugs block the release of the reproductive hormones LH-RH, therefore stopping ovulation and estrogen production.

Bilateral Oophorectomy. Bilateral oophorectomy, the surgical removal of both ovaries, is a surgical method of ovarian ablation. It may modestly improve breast cancer survival rates in some premenopausal women whose tumors are hormone receptor-positive. In these women, combining this procedure with tamoxifen may improve results beyond those of standard chemotherapies. Oophorectomy does not benefit women after menopause, and its advantages can be blunted in women who have received adjuvant chemotherapy. The procedure causes sterility.

Resources

- www.cancer.gov -- National Cancer Institute

- www.cancer.org -- American Cancer Society

- www.asco.org -- American Society of Clinical Oncology

- www.breastcancer.org -- BreastCancer.Org

- www.komen.org -- Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation

- www.nccn.org -- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- www.cancer.net -- Cancer.Net

- www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials -- Find clinical trials

References

American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: Breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;118(2 Pt 1):372-82.

American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 126: Management of gynecologic issues in women with breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;119(3):666-82.

Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Gass M, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women's Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012 May;13(5):476-86. Epub 2012 Mar 7.

Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012 Nov 22;367(21):1998-2005.

Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 18;356(3):227-36.

Burstein HJ, Prestrud AA, Seidenfeld J, Anderson H, Buchholz TA, Davidson NE, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Aug 10;28(23):3784-96. Epub 2010 Jul 12.

Casey PM, Cerhan JR and Pruthi S. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(1): 86-90.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: racial disparities in breast cancer severity - United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Nov 16;61:922-6.

Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2011 Nov 2;306(17):1884-90.

Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Gass M, Lane DS, Aragaki AK, Kuller LH, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2010 Oct 20;304(15):1684-92.

Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 434: induced abortion and breast cancer risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jun;113(6):1417-8.

Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012 Apr 18;486(7403):346-52.

Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, Evans DG, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, et al. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA. 2010 Sep 1;304(9):967-75.